60 seconds on the net

A few days ago, the folks at Qmee published a very interesting infographic. It gives us an idea of the real size and scope of the Internet these days. The social realm has given way to the electrical movement of information everywhere. The increase in speed isn’t due entirely to the improvement of information systems or technology based on new programming languages and object-oriented programming, or servers. The key thing in this change in mileage has been the socialization of everything.

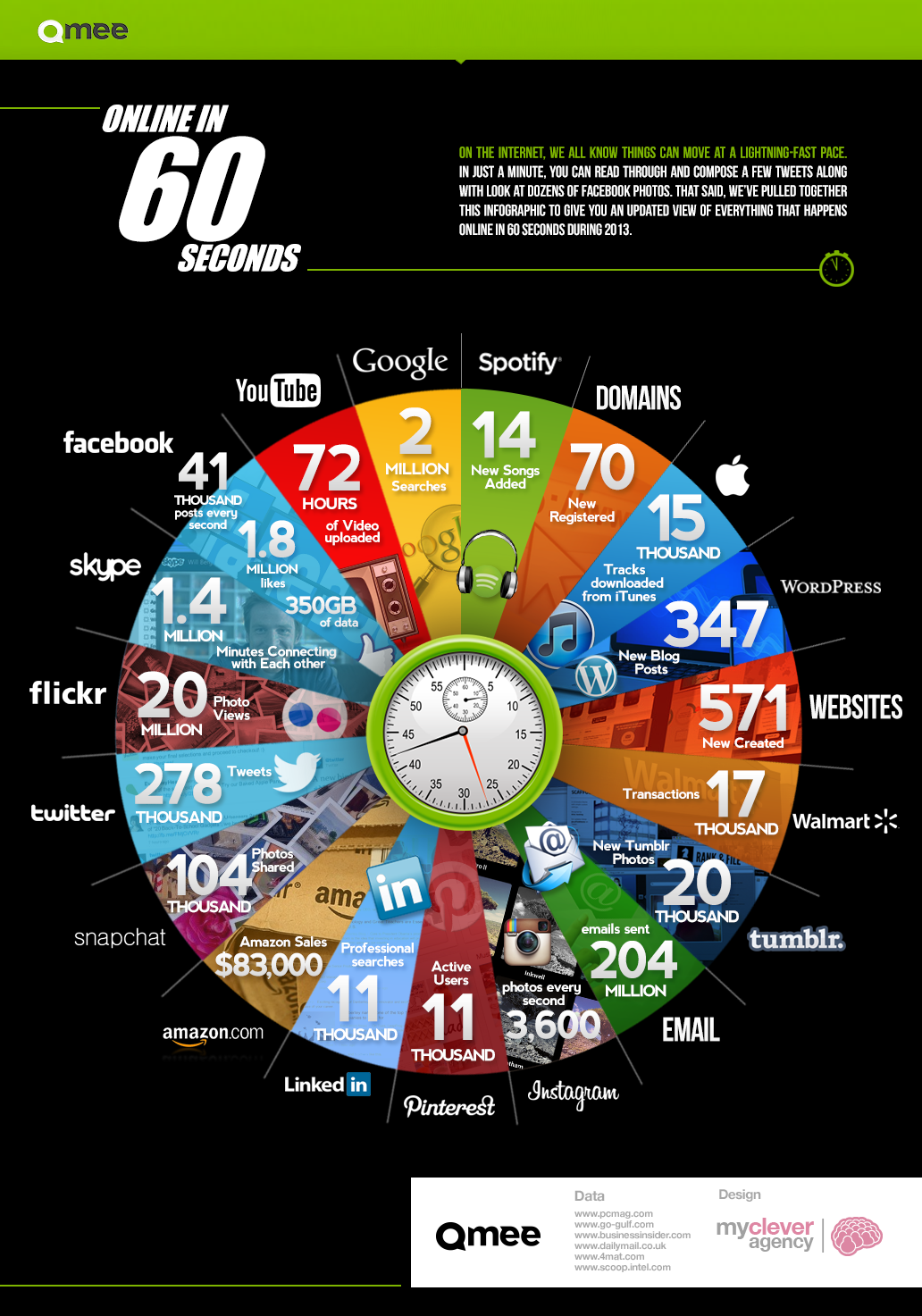

The activity that takes place online in just a few minutes is of such a dimension that it’s like when we look up to the stars and it makes us feel tiny. Everything around us keeps mutating, changing and processing the digital times we’re living in, and with luck that in turn will change and improve everything around us. It’s fascinating to discover that in barely 60 seconds, two million Google searches are made, or that 72 hours of videos are uploaded to YouTube. But with 204 million emails sent every minute, email is still king.

Startups, ‘hubs’ and my future

My friends warn me that travelling so much can’t be good. A little bit is fine, but this compulsive need can’t last my whole life. I don’t know, maybe they are right, maybe they are not. What I am sure of is that you learn while travelling, you become more intuitive and you are able to catch scents that you didn’t even know existed before. Regarding what I want to talk to you about today, travelling was key, and still is.

A few days ago a report was released that focused on some world cities of high interest in terms of startups or as technological hubs. It was an approximation of places that are not traditionally regarded as such. San Francisco, Berlin, New York, Miami, Santiago, Dubai, and Singapore didn’t appear in that report. On the other hand, they pointed out places like Amsterdam, Bangalore, Bogota, Dublin, Lisbon, Nairobi, St. Petersburg, Stockholm or Toronto. All of them have a clear positive pathway ahead of them, but each runs parallel to its own local crisis; all of them are focused on concentrating talent, digitalization, and the expectation of making their products global.

https://twitter.com/marcvidal/status/329534602739855362

In this list, there are three cities where IDODI and its spin-offs are already settled and have been working hard for quite some time. Bogota, Lisbon, and Dublin. Each one for a different reason, but all of them with something in common. It’s not easy, and whoever believes it will spend money and energy, since it’s a very twisted thing, but it’s doable. The key is knowing where and with whom you are going, to persevere, to be prepared for often feeling alone, and to be ready to eat all types of food. I like to think that having been stumbling around for so long, knowing first hand who does what and how they do it, what processes, protocols, and contacts you need in order to understand the rhythm of each place, has given me clear advantages in being able to place bets on locations with potential in the near future, despite any data saying otherwise.

We’re still planning to open a round of investments in June for almost ten different companies from the pool we manage or mentor; we have finished their development and in some cases they are already in production. Now, it’s curious that having received requests to be part of those startups I supervise, most of that interest comes from the countries mentioned in this link, way above the interest shown by investors from Spain. Development requires ideas, entrepreneurs, technology, and stimulus, but above all, it requires venture capital. If it doesn’t flow in one place, it will in another, and everybody will follow that flow positioning themselves in the ways they see fit, bringing relief of some, bringing glory to some more, and disgrace to the majority that always stay on their “couch”.

I’ve been travelling to Latin America for business for two decades. I’ve seen everything, and I hope to tell the story one day. I remember how Bogota was eighteen years ago and how risky it was to attend any event even in the best areas in the city. Mr. Alvaro Uribe explained to me that when he still was the President of Colombia, his dream was to set the foundation there for the future of the Silicon Valley of Latin America. He knew it depended on much more that his own work and he concentrated his efforts on bringing together different agents that are now the key for this technological model to expand and take root.

There’s evidence that the socioeconomic model is at stake at a planetary level. We can see how environments that have traditionally been far away from the digital and technological scene have slowly become part of it. It’s no longer required to have sophisticated research labs in order to develop disruptive technology. Now a connection allows you to travel thousands of miles, get training without leaving Dakar and start giving birth to an idea that, even though it may be a copycat of a more developed one coming from more advanced countries, can be adapted to the location’s idiosyncrasies and current technological needs. Keep an eye on the most powerful startups from the African continent.

I leave you by posting again a link to the selection of cities to take into account, titled “Emerging Tech: 9 International Startup Hubs to Watch”. Here are the nine international centers for technological startups that could be under the radar of any entrepreneur with international sights. These vibrant communities are more than places where startups are set up. They are total points of reference in terms of innovation and support, where inspiration and transpiration combine with business plans ready to be incubated. Opportunities arise and, most certainly, even entire markets are born around them. Whoever believes that internationalizing technology doesn’t require hub destinations is wrong. For countless businesses, just doing it any which way is the second mistake. We will talk about the adventures my team is having in further posts, in case it interests you.

Triple Challenge

In our company, we are both nervous and congratulating ourselves. We have put three new technological projects into production. They revolve around principles I consider key: they are scalable, they point towards a “long tail” generic market, and they are to be low cost for our clients. These products have been developed within IDODI’s own research program. From Dublin, we pulled the business development cart ahead and from Barcelona the technological project one. It’s been tough combining both efforts but it seems like things are starting to fall in place.

Even though we haven’t invented anything new, we seek to simplify processes, bring ecommerce to final users that scarcely use the technologies represented. We have tried for it to become a pool of products answering to the basic needs in the digital world today. Many more are still needed, and we are working on it.

They say investing on startups is risky. True. So much for all other “safe” investments out there, by the way. However, every time I have the chance, I’ll invest in models that allow job creation, chasing dreams, and facing changing times the way I see it. Not everybody needs to be able to see it, but they should be able to analyze it. These are the main characteristics of the items analyzed in this post:

We have three products. Openshopen, which allows you to easily and safely open an online store. I’ll comment on its outstanding features in coming days. Another one is Emailfy, which supports your online marketing campaigns and your online commercial mailing. The third one is Ebnto, which facilitates the easy organization and promotion of an event. All three pursue simplifying existing models, generate income if the user desires it and complement each other.

- We simplify similar models. We consider our offer to be efficient, complementary and international. We look forward to take this type of technology (with dozens of similar references) to shallower markets in which we already have very profitable commercial process going on.

- Generic international release. They are digital projects that can be sold without frontiers, but we release them using the commercial framework IDODI has in 17 countries as a base. On top of a great presence in Latin America, we provide presence in Singapore, USA, Portugal, and Ireland. This way we manage to close agreements and contracts with powerful local agents, accelerating the access to the greater public. This is not easy. Each branch, each team, each subsidiary represents a high cost in energy and money, involving a great deal of compromise and conviction. I must say it’s true we are helped by my almost two decades of networking while working throughout the world.

- Products in constant beta phase. I love releasing fully operational products branded with the label “on permanent improvement”. We are not going to stop learning and adding new elements. Many of the problems that may arise are being solved in real time, detected mostly through user experience. Is there a better model?

- Complementary, transversal, coordinated teams. My dream was to be able to have my own “software factory cloud”. A place were projects could be created taking advantage of synergies, teams, and challenges. That’s how we have designed this first plan. We’ve got three products because there are three companies, but all three are managed by a common staff and complementary teams. Very efficient patterns of what can be combined are created. I assure you it is not easy, but it is fascinating.

- Private capital. So far we haven’t had to engage in the process of attracting public funds. We haven’t requested a cent from anyone on top of what the partners been able to contribute. Maintaining the development of three products like these with dozens of people involved and complicated agendas is tough. Now it’s time to find capital for the coming stages once we get there. The funding rounds will be open shortly and, if you wish, you can request the proposal document at IDODI.

If, as a potential investor or client you interested in more information, don’t hesitate to contact me or my team.

Start-up creates really jobs

I read an article by Salim Furth on job creation and the new economy. You can find it at the Heritage Foundation. Who needs more than anyone to be innovative? An entrepreneur must face what is already on the market. You have no choice. Job creation is currently the Holy Grail for Washington policymakers. In order to craft better job policies, it is valuable to understand when, where, and by whom jobs are created. Rigorous data analysis tells us that start-up firms are disproportionate job creators and that new firms tend to appear in cities with smaller incumbent firms. Policymakers should keep future job-creating start-ups in mind whenever they hear an argument to protect the economic status quo.

Job Growth Through ChurningIn 2002, the U.S. Census compiled data on businesses going back to 1976 into the Longitudinal Business Database. By virtue of size, firms with more than 500 employees provide a large share of the jobs in the private nonfarm economy: 45 percent. Generally, larger sectors and industries see more jobs created as well as more jobs destroyed. The churning is part of a healthy economy, as long as gross jobs created exceeds gross jobs destroyed. From 1975 to 2005, economists John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda report that gross annual job creation was 17.6 percent of all jobs and gross annual job destruction was 15.4 percent, resulting in net job creation of 2.2 percent annually.

The firms that systematically create more jobs than they destroy are young ones. Sixty percent of the jobs created by start-ups still exist five years later. Haltiwanger, Jarmin, and Miranda note that “startups are a critical component of the experimentation process that contributes to restructuring and growth in the U.S. on an ongoing basis.”

Small Firms, Jobs, and Young Workers

Young firms are vital to growth. Two other papers show that concentrations of young or small firms are associated with higher subsequent growth across U.S. cities and across countries.

Haltiwanger, Jarmin, and Miranda emphasize that young firms are the most important net job creators. Since young firms are almost always small, a casual look at the data shows that small firms create many net jobs. However, deeper econometric analysis shows that the key feature is firm age, not firm size. Thus, we should expect roughly the same rate of net job creation from firms of equal age, regardless of their size.

Economists Edward Glaeser, William Kerr, and Giacomo Ponzetto go a step further. Knowing that entrepreneurial start-ups cause job growth, they ask the data where entrepreneurship occurs. Controlling for industry and region effects, they find that cities where the average establishment had fewer employees in 1992 had higher start-up rates there from 1992 to 1999. Thus, even if small businesses do not directly create jobs, they are a feature of a business environment that encourages entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurs do create jobs.

In a follow-up paper, Glaeser, Kerr, and Sari Pekkala Kerr dig deeper into the past and find that cities built near coal and iron mines tended to develop larger establishments and, therefore, to be less entrepreneurial.

Economists Ejaz Ghani, Kerr, and Stephen O’Connell confirm the same pattern in India. Using an Indian dataset that includes both formal and informal manufacturing firms, they find that young firms create jobs in India, too. Likewise, clusters of small firms are associated with more start-ups in the future.

Economists Paige Ouimet and Rebecca Zarutskie find that young workers are the group most likely to find jobs at start-up firms. In fact, they find that younger firms tend to offer better wages for young workers than older firms. And young firms seem to benefit from hiring young workers. Ouimet and Zarutskie suggest that some characteristics of young workers—such as their willingness to take risks—makes young workers a good match for young firms.

How It Works

Job creation and destruction occur in a highly complex, intertwined system. Glaeser, Kerr, and Ponzetto work to eliminate some possible explanations for the geographic correlation between average establishment size and subsequent start-ups. The link is not due to a city’s industrial composition, nor to general features of the city or region. They also rule out geographic differences in productivity and average age of incumbent firms, although those independently affect start-up rates.

The data leave two explanations standing: differences in fixed costs of starting a new business and geographically differing supplies of entrepreneurs. Regulatory hurdles, paperwork, and environmental restrictions, for example, can all raise fixed costs and discourage start-ups.

Policy Implications

New jobs come from new firms. New firms tend to appear alongside existing small firms. Given that these patterns persist in economies as different as the U.S. and India, it seems likely that the patterns of job creation represent fundamental economics, not a particular institutional framework.

Government can encourage job creation by making it easy to start a new business. Although large firms have lawyers working full time to help them navigate regulatory mazes, small businesses generally do not. The risk involved in entrepreneurship is ample; government should seek to remove barriers to entering business instead of erecting them.

Because incumbent firms and large corporations have the resources to lobby their representatives for favorable treatment, Washington policymakers often see persuasive arguments in favor of protecting the economic status quo. Where job creation is concerned, however, future start-ups are the champions, and they have no lobbyists.

The success and failure of startups are crucial mechanisms by which the economy organically encourages good ideas and discourages ones that do not meet consumers’ needs. Thus, although start-ups as a group create many net new jobs, individual start-ups frequently fail. Government should stay out of the business of “picking winners.” When a start-up based on a bad idea goes out of business, its capital and labor are freed up to better serve consumers.